Introduction

This is the first of two posts in which I offer a brief outline of my 7-year relationship with food and exercise since switching to a LOW-CARBOHYDRATE DIET. It’s long overdue and lends important context to what I write about elsewhere on The Durham Cow. I’m not a dietician, nutritionist or health professional and it’s not advice — it’s an account of my experience of the low-carb diet plus some of the PERSONAL OPINIONS that have endured in that time.

I’m happy to say that it’s been “fact-checked” by Diane, my wife, who has eaten the same way as I have, for the same length of time and in similar circumstances. Importantly, that makes us an “N=2” in scientific terms — two subjects who’ve shared a broadly similar protocol with regard to nutrition and other lifestyle aspects. I hope it makes it seem a bit more powerful than the subjective claims of a single person.

Since we switched in 2018 neither of us has “relapsed” nor has there been the least inclination to do so. I’m not inclined to jump straight into things — especially a subject as unpredictable as health — but I think that 7 years is long enough to wait before offering an opinion on what we — as a couple — eat and how it appears to have affected our health and capacity for activity, given that both of us are now in our 60s.

Also, I’d like to use this post as an introduction to sharing some of the features we feel have helped us in our low-carb journey — including favourite recipes. I’ll be happy to share or discuss evidence for any claims I’ve made but that’s not the purpose of this article which is merely intended to set the scene (maybe that can be done in subsequent posts if necessary). If, like me, you have doubts about the healthiness of a “conventional” diet, I hope it encourages you to do some research — as we continue to do.

My background

I started The Durham Cow a few years ago to document some of the natural and historic places I get to in the North of England and the ways in which I get there, usually hiking, cycling, and sometimes running. At that time I ate a conventional diet, the one still promoted by governments and health authorities around the world in which the main source of calories is plant-based carbohydrates: grains, fruit, vegetables, legumes (beans and peas), nuts and seeds — and processed sugar.

In retrospect it seemed that I managed fairly well but, on entering my fifties, I began to notice certain health-related issues including, but not limited to, decreasing mobility in the joints (particularly fingers); gastric issues including acid reflux which I combated with antacids, the long-term use of which is associated with numerous side-effects including potential damage to the gut microbiome; respiration issues which manifested typically as difficulty in taking what I considered to be a “full” breath.

Given that I’ve never smoked, I’ve mostly drunk alcohol in moderation and prefer not to take medications, I began to fix on the idea that diet could be a possible cause. I wasn’t alone either: my wife had her own reasons for taking an interest. So, sometime around 2012, we decided to simplify and freshen it — even discarding meat for a while. At the time I was also doing other stuff like fasted runs which, although uncomfortable at first, improved to an extent that made me begin to consider the metabolic relationship between eating and activity.

In 2017, by which time I was 55, I was running as well as I ever had been. I’m 5’ 8” and was then around 10½ stone or 65 kg (I’m about 69 kg today). While my weight seemed under control and a few issues had cleared up, others had emerged. I found myself thinking constantly about food and forever “grazing” (I couldn’t get enough breakfast cereal and dates). It didn’t seem ideal so I kept looking, and then Diane came across the “keto diet”.

The lowdown on low-carb & keto

Although it was new to me, the keto, or ketogenic, diet has been around — in one form or another — for over a century. In the 1920s it was used, very successfully, to treat paediatric epilepsy. Like the Atkins diet to which it’s similar, it restricts carbohydrates in favour of protein and fat.

The main three MACRONUTRIENTS in all diets are: carbohydrates, protein and fat. A typical western diet consists of around 60% carbs; 30% protein; 10% fat. Keto/low-carb reverses that to roughly ≤10% carbs; 30% protein; ≥60% fat (protein can vary depending on the diet but it’s the macronutrient that stays most consistent). Carbs can be further restricted (or increased) with fat always accommodating the difference.

Many people do well on Carnivore and Paleo diets which also exclude carbs to some extent. Carnivore excludes everything but the glycogen contained in meat while Paleo generally restricts anything that a paleolithic hunter-gatherer might not have eaten — including dairy.

I prefer the generic term “low-carb” to “keto” because I think it better describes what it actually is — for us anyway. It focuses on the component that, to me, seems to be the most problematic and which can most easily be manipulated or removed. I’m no fan of the word “diet” either — it’s simply the way I eat.

Fueling for exercise

The conventional approach to exercise nutrition relies on maintaining blood glucose levels from exogenous (external) carbohydrate sources, ‘dosed’ hour-by-hour or even minute-by-minute. The glucose introduced is used directly and helps maintain around two hours-worth of reserves stored as glycogen. Unless it’s individually monitored, this approach suggests to me that most people will take in more carbs than they need and lose little body fat either. It’s easy to see why there’s a MASSIVE INDUSTRY in sports “nutrition” and supplements.

Back in the day, the pockets of my cycling jersey bulged with bananas and cheese & jam sandwiches. As the 1980s gave way to the 90s so the sandwiches gave way to packaged gels, bars and chews with energy/electrolyte powders in my water bottles. The main ingredient in these highly processed products was SUGAR in one form or another. I’m of the view that the long-term price of this increase in sugar intake was declining holistic health (the sort of day-to-day problems that subtly persuade you to reduce exercise). These days my jersey pockets are empty and there’s only water in my bottle cage while I remain as active as ever.

Fat adaptation

Although there’s enough energy stored as fat in the leanest of athletes, to power at least a day’s worth of vigorous activity, if glycogen becomes depleted it’s effectively the end of the competitive road until replenished. If, however, the body has been allowed sufficient time to properly adapt to restricted glucose intake (by restricting carbs for a few weeks) it will COMFORTABLY METABOLISE FAT for use as a primary fuel source — even for vigorous exercise.

As well as metabolising energy directly from fat — a process known as lipolysis — the body also produces KETONES which help glucose to feed specialist cells and organs including the brain. Both of these pathways — enhanced lipolysis and production of ketone bodies — also help to SPARE GLYCOGEN (glucose). In the entire time that I’ve been on a low-carb diet I’ve NEVER run short of glucose no matter how long or how intense the exercise. I’ve yet to “bonk”, get “the knock”, “hit the wall” or even be hungry and I know that the same goes for the missus!

Once you’ve put in the groundwork and become stably fat-adapted we’ve found that there’s a fair degree of FLEXIBILITY. Occasionally eating something “carby” has no detectable effect. If I eat the bread that often comes with soup (even though I might specifically have requested otherwise) it has no perceivable influence on performance. Allowing carbs to creep back could be okay, to whatever level works for you. The mistake, in my opinion, is to re-establish a metabolic (and mental) reliance on them, particularly the processed kind.

Satiety and long term health

The MOST IMPORTANT characteristic of a low-carb diet as far as I’m concerned, one that’s often overlooked or ignored is SATIETY. Satiety is a feeling of sufficiency which should persist so that there’s no desire to “graze” or over-eat at the next meal. Neither should you be getting “hangry” (hungry/angry). If I feel like I want to graze — usually out of “boredom” (one of my least favourite words) — I’ll either do, or plan, exercise and the feeling passes. The body is rarely a problem but the same can’t be said for the mind.

I’m not saying that elite athletes don’t benefit from other strategies designed to get them past the post first but I’m not an elite athlete nor do I think that it’s necessarily healthy to be one. In fact, I sincerely believe that athletes — professional and amateur — are being encouraged to consume carbs in quantities that might possibly have negative long-term health consequences either directly or indirectly. My goal is to be AS ACTIVE AS POSSIBLE FOR AS LONG AS POSSIBLE and that’s all that really concerns me.

Carbohydrates

People might be surprised to learn that carbohydrates have been classified at NON-ESSENTIAL. They offer little by way of nutrition and are the only macronutrient that we can actually DO WITHOUT. Omit either protein or fat from a diet — for just a few weeks — and you’ll likely DIE. Do the same with carbs and — assuming you have plenty of the other two — you’ll THRIVE. Carbs do little more than provide “ready-to-use” calories in the form of simple and complex sugars. Processed carbs are typically so lacking in nutrition that they have to be supplemented or “fortified” with micronutrients.

Consuming carbohydrates increases blood glucose levels significantly, promoting the release of insulin which substantially LOCKS UP BODY FAT. Carbs introduce a bunch of negative physiological consequences for exercisers: erratic energy levels, gastric issues including vomiting, and weight control to name three. More importantly, to me at least, is their association with serious long-term inflammatory health conditions including insulin resistance, type-2 diabetes and other metabolic diseases.

Carbs are consumed in such quantity because they’re cheap, readily available and addictive thanks to modern farming, processing, preservation, supply and marketing methods. They’ve been developed to sustain POPULATIONS not individuals. If you see yourself as a “cog in a machine” then commercial carbohydrates are the fuel that makes you productive. I certainly don’t, and prefer to consume what I believe is an OPTIMUM SOLUTION FOR ME.

Fat

All sources of dietary fat contain saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated molecules — in different proportions. The idea that saturated fat is necessarily bad is a myth based on questionable studies that led to the so-called “diet/heart hypothesis” which came to prominence in the 1970s. Since then it has been perpetuated internationally by governments and organisations to promote the idea that carbohydrates should provide the overwhelming majority of calories in a diet.

Saturated fat has NEVER been proven to be responsible for heart disease as often claimed. The problem lies in its RELATIONSHIP WITH CARBOHYDRATES with the worst case scenario being a HIGH CARB/HIGH FAT diet. As long as nutritionally poor carbohydrates are promoted then less fat can be consumed which leads, at the very least, to a reduction in essential fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E & K.

Some fats — particularly seed oils used in cooking — ARE linked to negative health outcomes. They degrade dangerously at high temperatures (as in frying) while animal fats don’t. Oxidised seed oils are strongly associated with being carcinogenic. A phrase that’s stuck with me (I’m paraphrasing terribly) is “if you can’t press oil out of a plant with a lever, you shouldn’t eat it”.

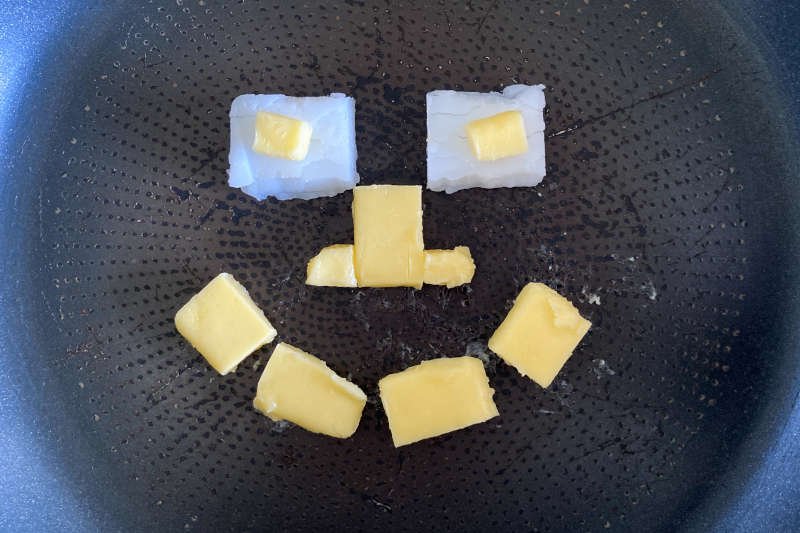

We also get through quite a bit of OLIVE OIL though we never use it for cooking; that’s only ever done with animal fat. One of the most constructive changes we made was to ditch the frankly ridiculous idea of coating the base of a frying pan with a thin spray of highly-processed “oil” from a bottle. Instead we reverted to doing as our grans did: using a dollop of dripping or butter. The consequences, so far, seem to have been entirely positive for us both.

Such a good job has been done over recent decades at indoctrinating people against fat that the idea of consuming it, particularly if it contains the word “saturated”, is a stopper for most. This “lipophobia” doesn’t appear to correlate with improved health outcomes either; metabolic sickness, including obesity, continues to increase despite far less fat being consumed. We’d fallen prey to the same propaganda, to the extent that when we took the plunge to switch we made sure to have annual blood tests all of which have been extremely reassuring when you learn how to interpret and compare them with other health metrics.

Fibre

The way I’ve come to view what’s officially classified as a NON-ESSENTIAL NUTRIENT is simply the UNAVOIDABLE CONSEQUENCE OF EATING CARBS. Its promoters insist that this indigestible plant material, in arbitrary quantities, is ESSENTIAL for gut motility, warding off cancer and other deadly misfortunes. It’s hard to understand therefore, why diets that restrict (and even exclude) grains, fruits and vegetables, plus the attendant fibre, aren’t significantly associated with poorer health outcomes. In fact, the strongest associations for all types of restricted carbohydrate diets appear to be with POSITIVE health outcomes.

As for our own toileting regimes, we can both confirm that there are no issues (I’d even say it’s a pleasure). My routine has been regular from the outset with well-formed stools that are easy to pass. Diane, who has a history of IBD (Inflammatory Bowel Disease) claims she’s been SYMPTOM FREE since being on a low-carb diet.

Micronutrients

As far as I’m concerned, recommended dietary allowances (RDAs) for micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) are also set for POPULATIONS. I think it’s unlikely that my prescription is going to be that of my neighbour given that my lifestyle isn’t typical of MOST people my age. We seem to lack nothing in our diet (and why would we) with tissues and neurological function seemingly AT LEAST as healthy as our peers. Even when tinkering with the idea of vegetarianism I never doubted that the most nutritious diets MUST be animal-based. Eating meat “nose-to-tail” together with oily fish and dairy categorically provides everything that’s needed to thrive, even vitamin C, commonly claimed to be missing from a low-carb diet.

While we eat do berries and some non-starchy, cruciferous vegetables, offal meat — particularly liver — is an EXCELLENT source of vitamin C but not one that’s well promoted. We also eat home-made FERMENTED foods like yogurt, kefir and kimchi. In his 1921 book The Friendly Arctic, the explorer and anthropologist Vihlhjalmar Stefansson lived amongst Inuit communities who had only meagre seasonal access to plants. Apart from fish, they lived for months on the organs and fat of seals and bears while the dogs got the majority of the less nutritious muscle. Many communities around the world still eat anthropological diets that are low in carbohydrates. None appear to be in worse health than their “western” counterparts.

Supplements

The low-carb market is a difficult one in which to sell supplements because it LACKS NOTHING. Exogenous ketones are aimed at the HIGH CARB market — for performance or recovery benefits I’d imagine though I’ve not found time to learn why exactly. There are SOME supplements though, a few of which we’ve tried out of curiosity but rarely getting beyond the first bag, batch or bar. Two notable exceptions are Xylitol and Erythritol both of which are natural sugar alcohols and essential in some recipes. HOWEVER, I’m intending to explore more supplements for the sake of this website. It’ll be an honest opinion though: if we’re not using them in our day-to-day diet then that will speak for itself.

Hydration

I’ve read quite a bit about how hydration might best be applied to a low-carb diet including types of fluid, quantity, frequency and additives. The truth is that 99% of the time, when running or cycling, I drink plain water (preferably carbonated when hiking). My approach is to drink only as much as I feel I need when I feel I need to. I’ve NEVER been a fan of preloading with water or pre-empting my need for it which has been the promoted strategy for quite a bit now. I do think it’s important though, to start any period of exercise PROPERLY HYDRATED. It’s probably best not to have been out on the lash the night before!

The only time I recall having a problem since switching to low-carb was a couple of years ago, during a hot club ride, when I lost my water bottle off a bridge in Staithes, North Yorkshire. There was no chance of retrieving it and nowhere to get water. I toughed it out but by the time I got some I’d become dehydrated and my performance was suffering badly (it felt just like “bonking”). Eventually though, I recovered and by the end of the hilly, 80-mile ride was going well again.

I think it would be remiss not to elaborate on the subject of alcohol. While I still enjoy beer, the maximum I’ll have in a single session is two half-pints — same for Diane with cider. We both drink wine, again much less than we used to — typically one to two medium glasses — occasionally in the evening or with a meal. I also drink whisky which I might prefer, on occasion, to wine. It’s been a very long time since I was anywhere close to being drunk and I certainly don’t miss it.

A few more myths

Here are a few more issues that are raised against a low-carb/keto diet, mostly by people who’ve never tried it:

- KETONES ARE DANGEROUS This is a popular one but the levels associated with “nutritional ketosis” (≤5 mmol/L) are much lower than the life-threatening condition of diabetic “keto-acidosis”. The two shouldn’t be confused. There’s plenty of evidence to suggest that some ketones may actually be PREFERRED by the brain.

- FATIGUE This definitely happens — at the beginning — along with occasional bouts of dizziness, usually when standing up from sitting. But it doesn’t last long because the body knows where it wants to get to and, assuming there are no underlying conditions, will resolve things within the first few weeks. Cyclists who’ve “bonked” will understand what it feels like. I’ll elaborate in Part II.

- IT’S EXPENSIVE Not as far as we’re concerned it isn’t and we’re by no means well off. It’s always a good idea to buy the best quality produce you can afford — as locally as possible. As far as we’re concerned, eating low-carb requires fewer meals, fewer ingredients and no supplementation. Shopping’s quicker as well: I like to visit certain aisles in the supermarket — particularly the cereals — just for old times!

- IT’S BORING If you’re okay with cooking then it’s as exciting as you want to make it. Admittedly it’s Diane who does the cooking because she likes it; I’m lucky enough that I’m easily satisfied in that regard. If you think it’s boring then it probably says more about YOU than the diet. On its own, starch is rarely more than bland “filler” that can be fashioned into shapes. These days, I’m inclined to think of ordinary white bread as “blancmange” — all of the taste and most of the texture is in fat and protein.

- IT’S HARD TO STICK TO This one’s a media favourite. After 7 years, one of the things about the diet that still freaks me out is how easy it was to cut carbs out of my life. It requires a little self-discipline in the first few weeks but once you begin to listen to the SATIETY signals from your body there’s no looking back.

That’s it for Part I. In the next part I’ll elaborate on why we decided to switch to a low-carb diet, what it’s been like and how we’ve adapted it. I’ll also give some pros and cons and offer a couple of practical examples.